Once upon a time in a land, well, not that far away, speed ruled the American turf. From pre-war wonders like Colin and Man o’ War to modern-day marvels like Ruffian and Affirmed, horses with the ability to dictate the tempo have always been hot commodities on U.S. soil.

All that changed in the New Millennium, specifically the mid-2000s. That’s when racetracks began implementing artificial, or all-weather (AW), surfaces on a grander scale than ever before. First, Turfway Park switched to faux dirt in 2005, followed by nearby Keeneland in 2006 and most of California a couple of years later, thanks to a mandate from the California Horseracing Board (CHRB).

Unlike dirt, all-weather surfaces tend to favor late runners, as exemplified by the great Zenyatta, who captured all 17 of her AW starts, most from well off the pace.

In fact, early speed became so irrelevant in Southern California in 2008-09, that the sight of jockeys hustling their mounts out of the gate was almost as rare as catching a glimpse of Mariah Carey in age-appropriate attire. At Santa Anita, for example, the rate of wire-to-wire winners at six furlongs fell from 38 percent in 2007, the last year the Great Race Place had a dirt main track, to 31 percent following the switch to Pro-Ride (one of several synthetic brands), according to longtime turf writer Noel Michaels.

What’s more, the blazing fractions and gaudy speed figures that were once a hallmark of Santa Anita and other dirt racing havens went the way of the rotary phone. Something else happened too, something far more insidious and difficult to spot — the American game changed. Due, in my opinion, to the influx of grass and all-weather races (which, as previously noted, stress late, rather than early speed) current U.S. jockeys on all three surfaces appear to have adopted the European approach, i.e. a moderate beginning followed by a flying finish.

In the 2006 book “Jockey: The Rider’s Life in American Thoroughbred Racing,” one of the country’s best reinsmen, Ramon Dominguez, described the Euro modus operandi beautifully while talking about his own riding style.

“Once we leave the gate, I want to get [my mount] relaxed and just take it as easy as possible,” Dominguez related. “I try to be patient, listen to the horse and let him go wherever he wants to go. If he wants to be last early, we’ll be last. If the pace is very slow, I’ll try and stay in touch with the field without rushing my horse.”

“Depending on how the race is developing, I’ll start going after them at the half-mile or three-eighths pole,” the champion jock added.

This trend of letting the horse determine its early placing continues to this day and it has had a pronounced effect on how races. Simply put, American racing has lost its mojo.

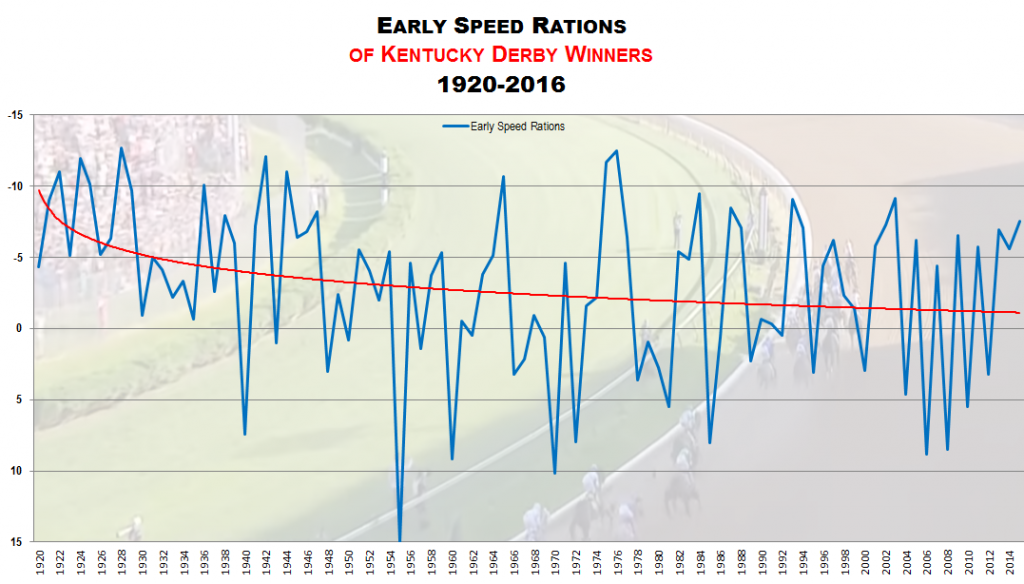

Nowhere is this more apparent than in the country’s greatest horse race, the Kentucky Derby. Since 1920, the Derby champion’s early speed ration (my own measurement of early energy disbursement, see below) has steadily increased (gotten slower).

In the 1920s, the average winning ESR was a brisk -9. That dropped to a -5 throughout the ‘30s and ‘40s and then settled into the -1 to -2 range for the next half-century. Starting with Giacomo in 2005, however, things began to change, as the Derby winner averaged a positive ESR through the remainder of the decade and the decade itself yielded the highest average winning ESR in Kentucky Derby history.

Now, I bring this up because, for the next several weeks, racing fans are going to be inundated with opinions on which horses can and which horses cannot get 10 furlongs on the first Saturday in May. Invariably, any steed that loses a prep after contesting the pace will instantly be regarded as suspect, while those gaining ground after lagging behind early will be considered prime contenders in the Bluegrass State.

Yet, it is interesting to note that Triple Crown winners — those gifted and lucky enough to triumph not only in Kentucky but in Maryland and New York as well — have possessed quite a bit of early lick. Combined, the 12 previous TC champs have recorded a -7 median ESR at Churchill Downs — considerably quicker than the historical norm of -3.

What’s more, the last sophomore to lead the Derby field from start to finish — War Emblem in 2002 — did so after recording an ESR of -6. Compare that to other recent wire-to-wire winners like Go for Gin (-9 in 1994), Winning Colors (-9, 1988), Spend a Buck (-9, 1985) and Bold Forbes (-12, 1975). You get the picture.

Hence, before tossing all the frontrunners in this year’s Run for the Roses, it might be wise to consider — at length — what the human connections are going to do and how the race might set up. Public opinion may not be on your side if you select a horse with early zip, but history is.