By Maryjean Wall

Lamplighter – Photo Courtesy of Speed Art Museum.

A mile and a quarter north of Churchill Downs stand some 160 horses of a different stripe than you’ll ever see racing again at an American track.

These are painted horses, done up in oil on canvas. They gaze out from their ornate wooden frames with a valuable knowledge of the past when they raced, trotted or competed in the show ring during the years 1825 to 1950. They are the story of America’s first professional sports intersecting with Kentucky history, and to tell this story the bar was high. Almost too high.

“For me it was how do I make some 160 brown animals exciting,” said Erika Holmquist-Wall, the Mary and Barry Bingham Curator at the Speed. Her job was to assemble the first-ever exhibition about horses the Speed has held in its 92-year history. She had 18 months to pull this together. She knew nothing about the state’s horse history when she began.

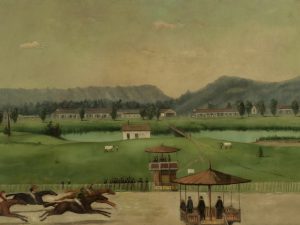

The Speed is Kentucky’s largest art museum and the question arose: why had it never presented the horse in a special show? “We don’t even own a painting of a horse,” said Holmquist-Wall. The Speed owned artwork of an early Louisville race course, Oakland Park. And it has lately acquired a painting of the old Latonia track, opened in 1883 in northern Kentucky. But no horses.

Now the Speed has gone from halls without horses to halls with a temporary collection that runs through multiple rooms. The collection, most of it on loan, is of famous equines who propelled the Bluegrass to prominence as a horse production center. Making this history interesting while telling it through art meant also telling the stories of the horses, of the people around them, of American historical events as they impacted racing, and even of the grass growing in Central Kentucky, as Holmquist-Wall learned.

The paintings and accompanying silver, drawings, manuscripts, and photos have a collective value in the millions of dollars. Holmquist-Wall and her team of two others networked with institutions and individuals to locate paintings. They discovered a painting of Tom Bowling that had not been seen publicly in generations. They learned much more about an obscure Victorian woman artist (Effie Leone Seavey Lucas) who painted horses and wore pants to the stables when women did neither.

“I’m not sure they know what they’ve accomplished,” said Genevieve Baird Lacer of Simpsonville, Kentucky, who loaned six paintings to the show and wrote an essay for the accompanying catalog.

“I’ve been researching this sort of material for 20 years,” Lacer said, “and to see it all play out from 1825 through 1950, through the art, for me it’s a dream. I’ve cried twice over it just because it means so much to have that information in a venue such as that.”

Old Latonia track – Photo Courtesy of Speed Art Museum.

Why the Speed took 92 years to present a horse exhibition remains anyone’s guess, considering the museum is a four-minute drive north of Churchill Downs. According to Holmquist-Wall, that fact of close neighbors might answer the question. Churchill Downs has the Kentucky Derby Museum. The Kentucky Horse Park in nearby Lexington has the International Museum of the Horse. No one wants to duplicate or overwork the same idea.

“Maybe (the idea of showing horse artwork) was just too close to our own back yard,” she said. “People take it for granted already.”

One question the show and its catalog had to deal with right away was: why Kentucky? How was it that Kentucky became centric to the American horse world of the nineteenth century?

Was it the (blue) grass? Something in the water?

Yes and no.

Early breeders recognized that the minerals leached by the soil, water, and vegetation imparted desirable health and strength to livestock. But more figured into the story. Multiple developments evolved into the perfect storm securing Central Kentucky’s claim as epicenter of the American horse world early in the 1800s. Kentucky temporarily lost this position in the latter 1800s as told in How Kentucky Became Southern: a Tale of Outlaws, Horse Thieves, Gamblers, and Breeders. But Kentucky received an invaluable head start prior to the Civil War of 1861-1865, and that helped Kentucky reclaim its place.

In a nutshell: the rich land attracted men of leisure who had time and money to devote to livestock breeding. U. S. Senator Henry Clay was one of the few exceptions. He was a lawyer, a working stiff, drawn from Virginia by the huge amount of lawyerly work he could see waiting in Kentucky. He made his fortune, acquired a farm and implemented the best practices of his day in breeding prize racehorses, donkeys, and other livestock.

Another was a physician, Elisha Warfield, who retired to pursue nothing other than breeding Thoroughbreds at his estate outside Lexington, called The Meadows. Men of this ilk knew one another for their common interests, got together in the early 1800s to form a local jockey club, and set in motion the forces that would attract more and more horse breeding activity.

“These were enlightened guys,” said Holmquist-Wall. “They were science-minded, business-minded, and entrepreneurial. It was lightning in a bottle, for sure. They had the means and the luxury of time and their status to be civic-minded, to be business-minded, and the (horse) industry developed out of their personal passions.”

The perfect storm.

The Finish – Photo Courtesy of Speed Art Museum.

The historical picture in the larger United States also made it possible for these like-minded men to pursue their passion for breeding horses. “Coming out of wartime, the war of 1812,” said Holmquist-Wall, “people are finally able to relax a little and that time was so precious that it nurtured all of that entrepreneurial spirit.”

Warfield bred the horse Lexington (whom he originally named Darley). He sold the colt and it raced at tracks from Lexington to New Orleans, while setting records and thrilling crowds of old time southerners and their slaves. Lexington went blind or nearly blind, was retired to stud at Woodburn Farm in Central Kentucky and became the most significant sire until Northern Dancer 100 years later.

These are the stories that unfold with the exhibition’s artwork and are told in the show’s catalog. Edward Troye was an animal portrait artist who painted Lexington numerous times after the horse entered the stud. Troye was like any of the animal painters of his time, in that he went from farm to farm as an itinerant artist, painting for commissions along with room and board while he worked. At Woodburn, where the larder was always full, he wore out his welcome. He was like the house guest who never left.

Troye also painted Asteroid at Woodburn Farm. Asteroid was undefeated and the best horse of his year but while waiting at the farm for the next season’s racing, he was stolen by Civil War outlaws in 1864. The bandits swam Asteroid and other stolen horses across the Kentucky River under a hail of bullets coming from pursuers off the farm. Eventually, a neighbor managed to negotiate the return of the valuable horse for a $300 ransom by telling the outlaws the horse was a favorite pet.

Troye’s “The Undefeated Asteroid” is among the paintings in the Speed’s exhibition. This one piece of art is interesting not only for its depiction of the horse but for the persons that Troye put in the picture. Riding in the background are the outlaws who stole Asteroid. The people surrounding Asteroid were three African Americans whose important role in building the horse industry did not begin to regain a lost appreciation until more than 100 years later. These were Ansel Williamson, a renowned trainer and former slave; Henry Overton, stallion supervisor at Woodburn Farm, and jockey Edward Dudley Brown.

Lexington was not stolen during that raid because the stable help just managed to hide him after the outlaws rode onto the farm. But it was close.

Will Harbut Leading Out Man O’ War – Photo Courtesy of Speed Art Museum.

These are just a few of the stories the art work relates. They also are the only depictions we have of these historic horses, their handlers, and a few of the tracks where they or other early horses raced. Remember, photography did not exist during the early development of the horse industry.

The catalog and artwork tie together other developments along a timeline of horse history intersecting with Kentucky history. One of these was the historic match race in 1839 between Wagner, representing the South, and Kentucky-bred Grey Eagle, based in Louisville and representing the North. Interest in the match was high across the United States during this era when South and North were hard at each other’s throats. Attention over this North-South horse race helped put early Kentucky on the racing map. Wagner won the match, then won a rematch called for after Grey Eagle’s owner could not believe his horse got beat. The matches were held at Oakland Race Course, a predecessor of Churchill Downs which did not open until 1875.

The Speed’s exhibition travels through the decades, then comes to a halt at 1950 just when American racing was in its glory years. Holmquist-Wall said this seemed a good stopping place because by 1950, “literally we ran out of room,” the curator said. “After 1950 you start getting into a lot of commercialization of equine and sporting art and it became harder to parse the museum quality artwork,” she added.

While walking through the halls of horse paintings, it was easy to see how the exhibition turned out to be a worthy addition to an afternoon at Churchill Downs’ fall meet. But as Holmquist-Wall said, “There is much work to do, and many stories to tell.”

It might take another show to do it all.